Russian Icons

Home

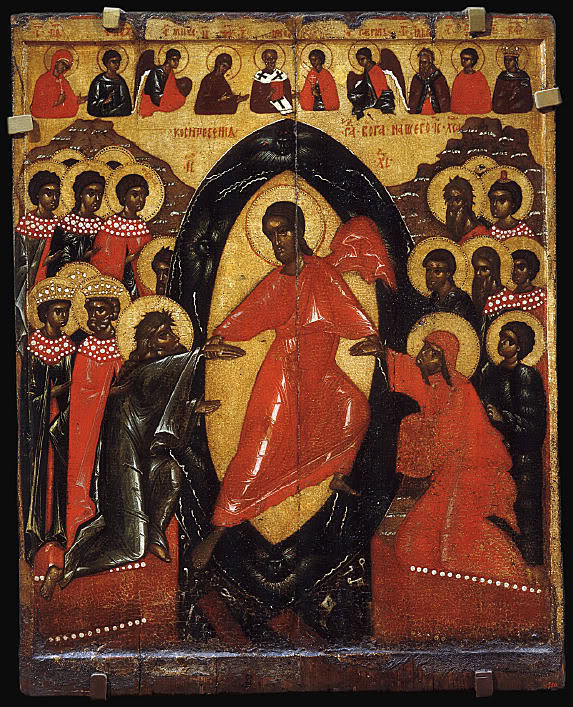

Anastasis (Descent into Hell)

Notes:

The Anastasis (Descent into Hell)

Pskov

Christ's descent into Hell (Anastasis) is believed to have occurred after the Crucifixion and before the Resurrection. In this mid-sixteenth-century icon from Pskov, Christ, showing that his sacrifice redeems the righteous, rescues Adam and Eve.

The composition of this icon, rather typical of sixteenth-century painting, originates in certain styles of the Byzantine period. The icon has been dated to the late fifteenth century by Konrad Onasch and to the early sixteenth century by a group of earlier scholars and other later authorities. Those who accept the latter date also believe the icon was made in the provinces of Novgorod, perhaps Vologda.

The artist of this icon links the crucifixion with the descent into hell -- a bonding of the historic and the symbolic. These elements are given aesthetic continuity by a series of alternating short diagonals that vertically stitch the passages of the composition into parallel columns of zig zags or steps. As Christ's form bends, so do the parenthetically posed figures of Adam and Eve to his right and left respectively; so, too, do the echoing hills which loom above the scene.

The slightly bending posture of Christ raising Adam by the hand, the kneeling Eve, her body and hands draped in the "maphorion," (cloth wrap or cloak) and the groups of dead on both sides beholding the scene are characteristic of the iconography associated with the Anastasis. The golden robe of Christ symbolizes the light of salvation that the Savior brings to those who have died. In this icon, Christ's light beams into the underworld, a gift to the resurrected.

Christ is presented against the great mandorola, a symbol of divine perfection. The mandorola was employed earlier in the century by Dionysus (see the other icon by the same name in this ImageBase) as a compositional element of his "Descent into Hell" in the cathedral of the St. Ferapontov Monastery. The circular mandorola, also symbolizing glory and truth, appears many times as part of the iconographic ensemble in sixteenth-century Russian painting.